Objectively, the fall of Constantinople in 1453 AD was a significant turning point in the history of mankind. Some argue that it was when the light of Rome was extinguished forever. As the last Byzantine Emperor, Constantine XI Palaiologos, ran off into battle to face the Ottomans, he, like the empire he ruled, faded into the annals of history. It makes for a nice tale: the city was founded by Constantine the Great, and it ended with Constantine XI. Yet it does beg the question of why does the story of Rome end there? Why aren’t the Ottomans considered the heirs to the Roman Empire? Thus, I will make the case for why the Ottomans should, at the very least, be part of this conversation.

The Sad Reality

Firstly, we need to acknowledge the very poignant political reality that from the moment Odoacer entered the city of Ravenna in 476, the title “heir to Rome” had little actual meaning. Firstly, there was still a Roman Empire in the East with an emperor ruling from Constantinople as it had been since Diocletian split the Empire in two. The only reason we even use the term “Byzantine” is because later Renaissance writers wanted to believe that they were the first to reconnect with the glory of Rome. Secondly, the concept of being ‘emperor of the Romans’ was more about having political hegemony, especially in pre-Reformation Europe, where the Catholic Church was the one and only legitimate religious authority. Even by the time Mehmed II marched on the city of Constantinople, the Eastern Roman Empire was essentially non-existent, unable to really project significant political authority anywhere outside of its capital. Ironically, this truly started under the Fourth Crusade, which sacked the city and never really gave it a chance to recover. In many ways, the Ottomans’ cannons were more like euthanasia for the ‘sick man of Europe” than a destructive conquering force.

The Religious Argument

Now that we have undermined the concept of an ‘heir to Rome’, let’s actually examine why the Ottomans deserve to be included in the conversation. Let’s begin by examining religion. Yes, the Ottomans were Muslims who prayed toward the city of Mecca, not Orthodox Christians who obeyed the Patriarch in Constantinople, yet this was not the first time Rome had changed religions. First, there was the Great Schism of 1054 AD, which led to two different people claiming religious authority. The Pope was Pontifex Maximus, had a title shared with the emperors (and thus the true leader of Rome). Yet, the Byzantine emperors rejected this claim, seeing it as associated with paganism. The switch to Christianity itself represented a departure from the Roman pantheon. To a Latin-speaking man from the hills of Rome like Augustus, who gave sacrifices to Jupiter, there would be no difference between Justinian, a Greek speaker from the Balkans who worshipped Christ and Mehmed, a Muslim Turk. Fundamentally it is clear that the political institutions mattered more to be able to claim descent from Rome.

Ottoman vs Roman Territory

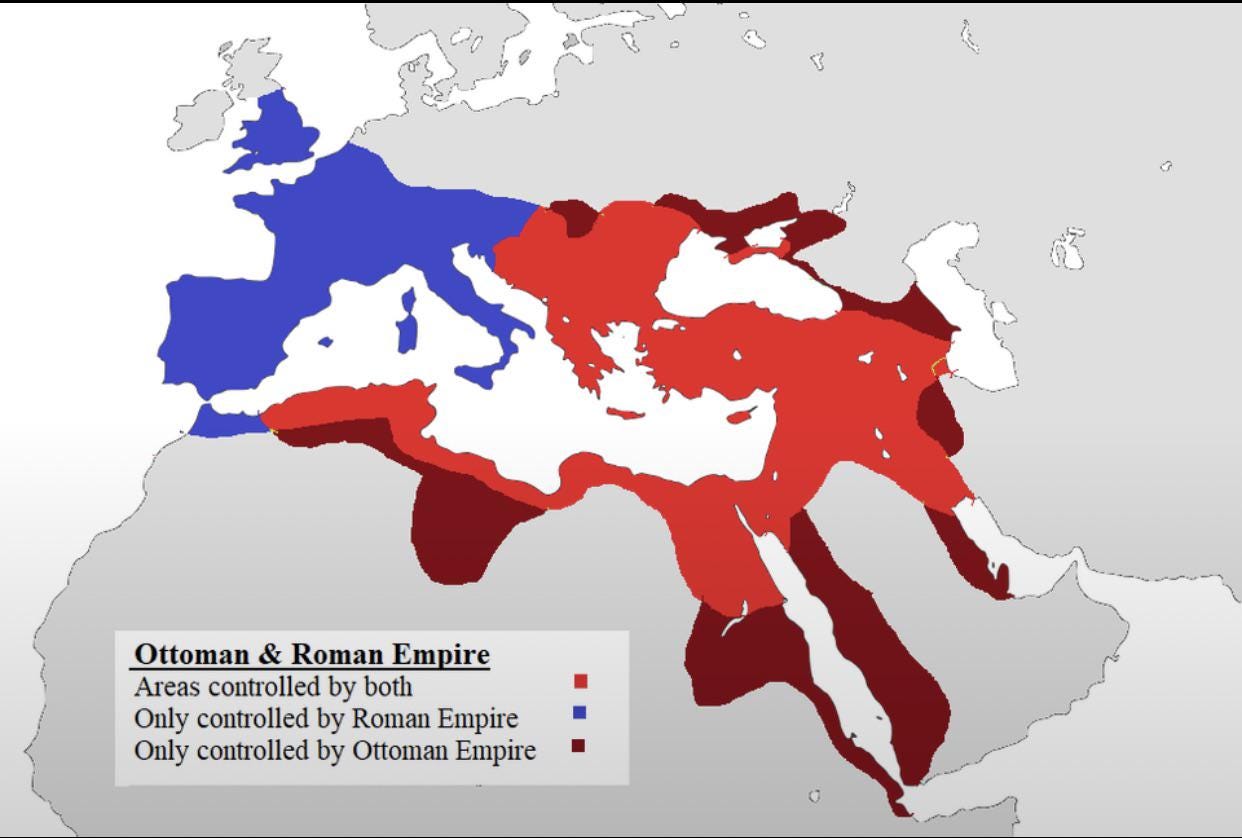

Then, you have the geographical claim. Despite the efforts of Belisarius and Justinian I, at its height, the Eastern Roman Empire controlled about 50% of former Roman territory. This is in large part due to the Ottomans' complete control of the Arabian peninsula, which they did not lose until the empire’s collapse in 1918, as well as control of significant parts of North Africa and even threatening Iberia at times. The longevity of their respective conquests is also important to consider; the Ottomans survived until 1918 and managed to hold on to parts of North Africa as late as 1912. In contrast, the Byzantines fell far more quickly. Not to mention other claimants like the Holy Roman Empire, which due to its decentralised nature, lacked the ability to consistently assert military dominance.

From Provinciae to Eyalets & Honouring the Past

There is also the administrative claim, the Ottoman sultans were the caliphs of their day, claiming to be the successors of the Prophet Muhammad ﷺ, not unlike how the Caesars claimed the title of pontifex maximus. The rulers of the Ottoman Empire also claimed the titles of kayser and basileus, asserting that they viewed themselves as the rulers of Rome. They also copied the Roman style of governance, in the sense that they kept the system of provinces. Additionally, Mehmed the Conqueror was a learned man who greatly respected Roman traditions. He spoke both Latin and Greek and even visited the grave of Achilles. Despite turning the Hagia Sophia into a mosque, he treated it and the other wonders of Constantinople with great respect. Reportedly, he threatened to kill a soldier whom he caught looting the building. Moreover, the Ottomans kept the name of Constantinople, referring to the city as Kostantiniyye. The Ottomans also treated the city with great respect, which is more than can be said for the Latinate crusaders who sacked the city in 1204. It became a central part of Ottoman identity, and during the Turkish War of Independence, great lengths were taken to recapture it.

Thus, here is the argument for why the Ottomans should at least be considered heirs to Rome. Not only were their religion and ethnicity no more different from Augustus’ than any other claimant's, but they also held onto Roman territory the longest and treated Roman culture and heritage with great respect.